THE Olympics. The greatest sporting spectacle that ever was. The chance to win it all.

There is no silence in the velodrome. No stillness. Except for on the track, where the best of the best from around the world line up and await the firing of the start gun. Every ounce of concentration pools to the front of their minds as the heart reaches its anticipatory rise. Muscles tense. Pedals stabilise.

Bang.

The cyclists remain still.

Bang. Bang.

But there is one cyclist in the line-up that is experiencing a mass of internal gunfire. Her concentration splits. Teeth grit.

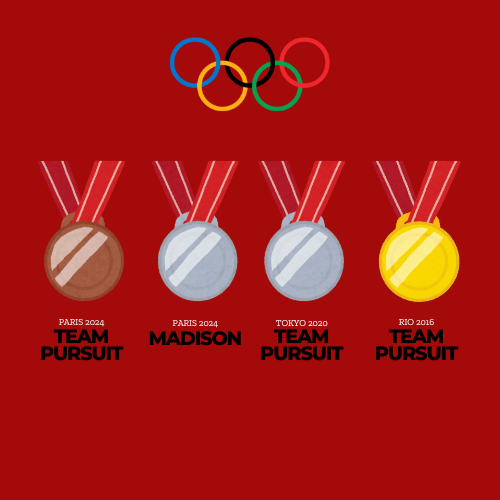

At the 2024 Paris Olympics, Elinor Barker MBE became Wales’ most-decorated female Olympian.

She won silver in the Madison and bronze in the Team Pursuit.

But these Olympics were post-pregnancy and post-laparoscopy to treat her endometriosis.

The surgery works by making small incisions in the abdomen to remove endometrial tissue with small tools.

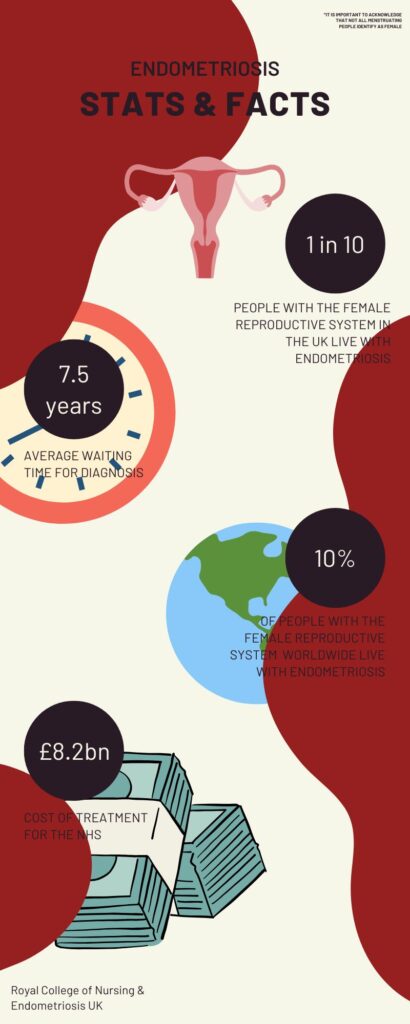

Endometriosis is a condition where endometrial tissue grows outside of the uterus, causing severe pelvic pain, fatigue, cramping, and irregular bowel movements.

Without treatment, endometriosis can last from the first period, all the way to menopause.

In the UK, one in ten menstruating people live with endometriosis, however the average waiting time for diagnosis is up to 7.5 years (Royal College of Nursing).

7.5 years.

“Pre-diagnosis, I was in quite a desperate state,” Barker said on her condition. “I felt that I had a lot more abdominal pain than most other girls seemed to, but every doctor wrote it off as normal for years.

“By the time I got a diagnosis, it had progressed to the point where I was losing full nights of sleep and missing training sessions due to the pain.”

Barker’s first Olympic medal was won in the 2016 Rio Olympics, after winning gold in the Team Pursuit with teammates Laura Kenny, Joanna Rowsell and Katie Archibald. In 2017, she received an MBE in the New Year Honours for her services to cycling.

However, Barker was fighting against the symptoms of an as-yet undiagnosed condition throughout the competition and in their pre-Olympic training programme.

“It was having a huge impact. I couldn’t train properly, and it was affecting my sleep and my diet.

“My recovery was terrible, and I felt so fatigued by being in pain, and also trying to cover it up.”

The first ever laparoscopy to treat endometriosis was performed in 1989, and Dr. Robert L. Barbieri later discovered the CA-125 glycoprotein to be a potential biomarker for the condition.

Erin Bradshaw, a research assistant at Monash University in Melbourne, wrote for The Conversation: “Press coverage of diseases plays a huge role in the public’s understanding of a disease.”

In the UK, endometriosis affects 1.5 million people that were assigned female at birth.

But due to the stigma of ‘it’s all in your head’, Endometriosis UK reported that 54% of people in the UK are unaware of what endometriosis actually is.

They also noted that many workplaces do not recognise endometriosis and its impacts, and that overall, it costs the economy £8.2 billion per year through treatment and knock-on effects.

Barker was fortunate to receive private treatment through British Cycling, as well as through the NHS.

“I sought advice from as many specialists as I could, until one eventually recommended surgery for suspected endo,” the Welsh cyclist said.

“The fatigue from being in pain for multiple days was really hard to push through, especially when it affected my appetite and ability to do basic things to look after myself.”

Imagine.

There are conditions that are naturally non-visible, and then there are conditions that are forced to stay non-visible, either through internal or external pressures.

“I worried it would make me seem like an unreliable athlete and affect my selection chances if coaches knew,” Barker continued.

“I didn’t really consider quitting the sport, but I did expect that if I didn’t find a way to fix the problem, then I wouldn’t have a very long career at all.”

Unfortunately, surgeries aren’t always smooth sailing and, as a condition, endometriosis can lead to complications.

“It wasn’t the magical cure that I thought it would be. Most of the endometrial tissue was connected to nerves.”

As Team GB took the short flight to Paris in the summer of 2024, following behind them was Barker’s husband and two-year-old son, Nico.

Interestingly, pregnancy used to be a suggested form of ‘treatment’ for endometriosis and a way to reduce symptoms.

However, Barker was able to train throughout her pregnancy and be fully fit to compete at her third Olympics.

On her physical ability going into the Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines velodrome, Barker said: “I’ve found I haven’t had many problems at all, and it’s not something I think about at all anymore, so I feel like I can push my body and focus on my performance.

“You only get short appointments, so I was often referred for the same tests when I saw somebody new, which felt like a waste of time.”

Her advice to young athletes suffering from endometriosis?

“I think be persistent and get different opinions. I would also make sure you keep good records of any appointments you have so that you can show them at your next appointment.”

Upon the conclusion of the indoor cycling events in Paris, Barker would be set to fly home with two more medals to add to her cabinet.

Since her first Olympics back in 2016, she has become accustomed to the hype. To the thrill. To the challenge and the success.

Athletes are still human, firstly, despite their abilities that make them seem superhuman.

In Elinor Barker’s case, it is the human challenge and the valiance in the hidden battle that speaks louder volumes than the noise projected from the velodrome stands on race day.

This feature is part of a collection, titled: Non-visible disabilities in mainstream sport

Feature 1: El Reid | On The Ground

Feature 2: Beth Dobbin | The Things You Don’t See

Feature 4: Matt Graves | Still Human

Feature 5: Emma Whitlock | Mind Minefield